Jirsch Sutherland Partner Lloyd Kerr has a simple message for accountants and directors undertaking a Members’ Voluntary Liquidation (MVL): don’t forget to lodge the company’s last tax return.

“It’s the bugbear of many insolvency practitioners and it can delay the process – particularly the distribution of dividends to shareholders,” Kerr says. “Accountants handle the tax, we don’t. So, before you hand everything over to a liquidator, get your paperwork in order.

“Delaying an MVL could see shareholders waiting for the ATO to clear a backlog. MVLs do tend to take longer than, say applying to deregister a company voluntarily, so it’s always advisable to start the process as soon as the decision is made to avoid delays. And make sure the final tax return and any other relevant taxation lodgments have been lodged, even if the company isn’t trading.”

Kerr adds that before giving an MVL to a liquidator, accountants should also do any necessary “digging”. “For example, finding the origin of the make-up of any reserve balances or capital gain balances on a company’s balance sheet. Don’t give a liquidator a balance sheet with minimal detail. Get the paperwork in order first.”

Why MVLs

An MVL is an option available to a solvent company whereby its members can liquidate the company’s assets and wind up its affairs, distributing any surplus assets to members before it is formally deregistered.

This may be for several reasons such as the company has ceased operations and the directors/members no longer have a use for it; shareholders want to access the company’s equity in a tax-effective manner; or the ongoing compliance costs of lodging reports with ASIC are too high. (Even if companies stop operating, they are still a registered company and need to lodge documentation with ASIC and the Australian Taxation Office and pay an annual registration fee.)

MVLs also tend to cost more than applying for deregistration, although the potential tax savings generally outweigh this downside.

MVLs differ to a Creditors’ Voluntary Liquidation (CVL) as they involve a company that is still solvent, while a CVL involves the closure of a company that is insolvent – although this process is still undertaken voluntarily. Once an MVL is finalised, the proceeds of the sale go to the shareholders; with a CVL, the cash realised from the sale of assets is returned to creditors.

Kerr says one of the tax benefits if that a shareholder may be able to access various tax concessions. Kerr says MVLs are very tax effective at returning assets and dividends to shareholders. “They are often useful in situations where control has passed through inheritance and that control has been diluted,” he says. “It enables an independent person to handle any distributions.”

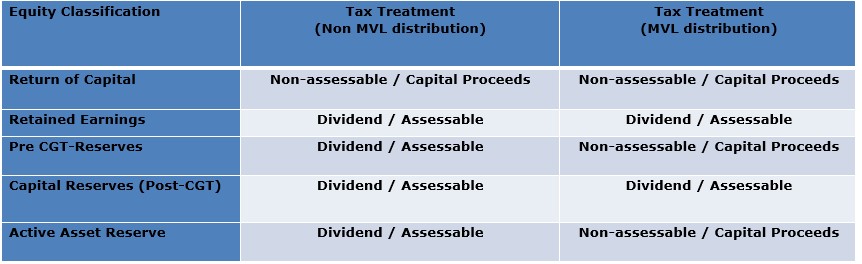

Below is a table setting out the tax outcomes to shareholders comparing a normal distribution vs a dividend distribution via an MVL.

End of year rush

Kerr says that March to May traditionally sees an increase in MVLs as directors and their accountants voluntarily wind-up companies before end of financial year – and this year is no exception. “The majority of MVLs are family companies whose shareholders are mums, dads and their children, or they are other simple affairs. For example, I handled an MVL for a man in his 90s whose company owned investment properties and shares worth around $3 million, and he wanted to tidy up his affairs rather than leave it to his executors to manage.”

He adds that Jirsch Sutherland also handles what he describes as “live and interesting” matters, such as a long-established and solvent winery, and a big multi-generational trucking business whose next generation didn’t want to run it.

“These tend to be more involved and take a longer time than the ‘tidy up’ liquidations of non-trading companies,” Kerr says. “Regardless of the size and complexity, one simple takeaway remains – don’t forget to lodge the last tax return.”